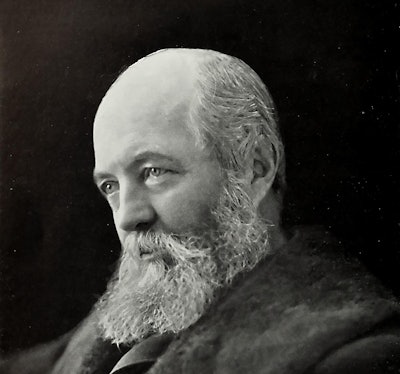

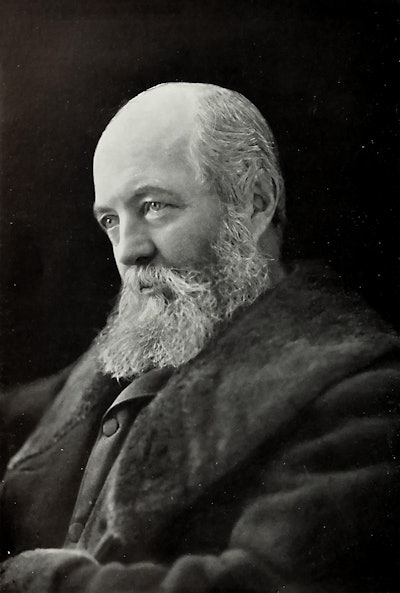

Frederick Law Olmsted lived from 1822 to 1903.

Frederick Law Olmsted lived from 1822 to 1903.Frederick Law Olmsted is considered the father of American landscape architecture and some of his best-known works remain iconic to this day.

Central Park and Prospect Park in New York, the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., and Biltmore Estate in North Carolina are just a few of the thousands of parks Olmsted designed.

Throughout his career, he followed a set of design principles that would ensure his landscape architecture projects would endure for years to come.

Here are 10 of his principles and what they mean:

Respect “genius of the place”

Olmsted believed in staying true to the character of the space. “The genius of a place” is the idea that each location has unique qualities, both ecologically and spiritually. His goal was to infuse this into all design decisions by acknowledging the advantages and disadvantages of a site.

Subordinate details to the whole

One of the ways Olmsted strived to differentiate landscapers from gardeners was the elegance of design. He preferred not to think of trees, turf, rocks, and water as things of beauty in themselves, but merely thread in a larger fabric. He chose to avoid decorative plantings so the landscapes looked more organic and natural.

The art is to conceal art

For Olmsted his goal wasn’t for visitors to see his work, but rather to be unaware of it. He wanted to free the viewer’s mind from distractions. They weren’t supposed to analyze the space, but be unaware it was planned at all.

His designs were so natural one critic said, “One thinks of them as something not put there by artifice but merely preserved by happenstance.”

Aim for the unconscious

A similar design concept, Olmsted liked for his scenery to work on the unconscious part of the mind. He constructed parks that subtly directed movement through the landscape. Pedestrians are led without strict, noticeable guidelines and one could feel lost but know their way out at the same time.

Avoid fashion for fashion’s sake

Olmsted was not a fan of flashy novelties in the landscape or decorations that served no purpose. He thought of specimen planting and exotic species as intruders. He argued that while a planting of wild flowers may not draw attention to itself, it may be more effective in soothing and refreshing the mind.

Formal training isn’t required

Olmsted did not commit to landscape architecture until he was 44. He had no formal design training and previously worked as a correspondent for the New York Times, a California gold mine manager, and Executive Secretary of the U.S. Sanitary Commission.

He gathered his knowledge of landscaping from traveling and reading. He voyaged to China, Europe, and the British Isles and saw many parks, private estates and the countryside.

Words matter

Olmsted was prolific writer and strongly opposed the term “landscape gardening,” feeling that his work had a much broader scope.

“Gardening does not conveniently include exposing great ledges, damming streams, making lakes, tunnels, bridges, terraces and canals,” he wrote.

Stand for something

By the time Olmsted had committed to landscape architecture, he had developed a set of social and political values that gave extra purpose to his design work. A series of influences convinced him the importance of aesthetic sensibility as a way to move American society from the frontier lifestyle toward what he considered a more civilized condition. He believed in community and the importance of public institutions of culture and education.

“It is one great purpose of the Park to supply to the hundreds of thousands of tired workers, who have no opportunity to spend their summers in the country, a specimen of God’s handiwork that shall be to them, inexpensively, what a month of two in the White Mountains or the Adirondacks is, at great cost, to those in easier circumstances,” Olmsted wrote.

Utility trumps ornament

Service always came before art in Olmsted’s work. He felt that when plants and trees had no purpose it was “inartistic if not barbarous.” For him, true art was achieved with utility was considered first before ornamentation.

He preferred to use sustainable designs and plants that required little maintenance. Olmsted strived to preserve the natural site and maintain the ecological health of the area.

Never too much, hardly enough

Rather than packing a site in with so many sights and sounds viewers would be overwhelmed, Olmsted chose to simplify and clear the scene.

Critics accused his work of being unkempt and rough but Olmsted knew what he didn’t do was as much a design choice as what he did do.

He told his ex-partner Calvert Vaux thirty years after they completed Central Park, “The great merit of all the works you and I have done is that in them the larger opportunities of the topography have not been wasted in aiming at ordinary suburban gardening, cottage gardening effects. We have let it alone more than most gardeners can. But never too much, hardly enough.”