Nowadays most of the population uses social networks to keep in contact with friends and family, and it turns out humans aren’t the only organisms using social networks.

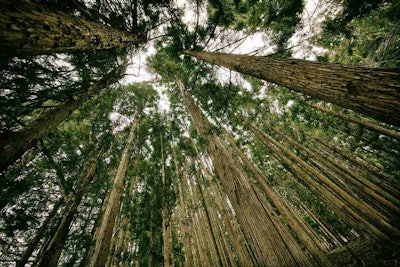

Research from Suzanne Simard, an ecologist at the University of British Columbia, has revealed that trees are able to cooperate and share resources through an underground network of fungi.

An example of this mycorrhizal network, a symbiotic association between a fungus and the roots of its host plant, is how fir trees receive carbon from birch trees in the summer, but in the autumn birch trees receive carbon from the fir trees.

“A forest has an amazing ability to communicate and behave like a single organism – an ecosystem,” Simard told CNN.

Aside from connecting trees to one another, fungi receive sugar and carbon from the trees and in return the fungi release phosphorous, nitrogen and water to the trees.

Trees can communicate through the network by sending chemical signals into the fungi. Trees that are attacked by bugs will send the signals and neighboring trees will take note of these signals and increase their own resistance to the threat.

Botanist Stephen Woodward from the University of Aberdeen prefers to see this as a mere adaptation for survival, rather than a communication method, yet the benefits of the network remain the same.

Certain older trees serve as “hub trees” and are better connected in the fungi network. These hub trees send their excess carbon to help developing seedlings. According to Simard, the presence of hub trees can increase these young trees’ chance of survival fourfold.

Hub trees also help forests adapt to climate change thanks to their considerable age.

“They’ve lived a long time and they’ve lived through many fluctuations in climate,” Simard said. “They curate that memory in the DNA. The DNA is encoded and has adapted through mutations to this environment. So that genetic code carries the code for variable climates coming up.”

Simard argues that it is important to preserve older trees and maintain diversity in forests rather than growing plantations of one or two species.

“We look at them as a bunch of trees competing with each other and forestry practices are all built on that premise,” she said.