Photo: SnowEx

Photo: SnowExYesterday, we covered the pros and cons of salt brine as well as the common misconceptions surrounding them. Today, we’ll take a look at some of the best practices when it comes to adding this tool to your snow removal practices and when you should consider adding brine making to your operations.

Best practices for applying salt brine

Other brines like magnesium chloride and calcium chloride are hydroscopic and tend to draw moisture out of the air, creating adverse conditions by diluting the liquid, if there’s a lot of humidity in the air.

“There are some tradeoffs there,” Birch says. “But they tend to melt snow and ice or lower the freezing point of water to lower conditions. So, a lot of practitioners in the commercial market use a calcium or a mag chloride brine to manage the work.”

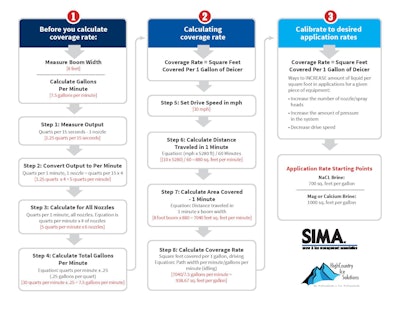

Another fundamental aspect of properly applying brine is to have calibrated your equipment and use the right application rates.

“A key variable here is application rates and how much liquid do you put out on the pavement,” Birch says. “If you put too much, it can runoff. It is wasteful, and it can cause adverse conditions. If you put too little, especially when you’re just starting, you may not see the response you want. You may think it’s not working and have to go apply salt. You may get pushback from the customer, which is already tough if you sold them on this new process.”

Birch says calibration comes down to the size and pressure of your systems, the type of product you’re using and the required amount to melt snow effectively. He advises getting your equipment dialed in at the beginning of the season.

Graphic: SIMA

Graphic: SIMA“If you work through those variables, you have to calculate what your flow rate is per one nozzle and then you have to multiply that by the number of nozzles you have,” Birch says. “You calculate an output rate for your spray rig just standing still for, say, 15 or 30 seconds and then from there, you have to calculate the spray path over a certain length and what that coverage is. You can control that coverage by ground speed and pressure.”

Greg Stacho, snow manager for Level Green Landscaping based in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, advises talking to your local supplier for help calculating your proper application rates. He also says a general rule of thumb is one gallon will cover 1,000 square feet.

“Following application rates will result in large decreases in chlorides runoff into streams and waterways,” Stacho says.

Birch says there is no set application rate that will work for every location, so contractors have to work through it and see what suits their jobsites.

“Everybody needs to experiment and see what works best for them and their lots,” says Rick Kier, founder of Pro Scapes, based in Syracuse, New York. “I can tell you, different types of pavement react differently to brine.”

Kier says you should take careful notes and pay attention to the results you get on customers’ properties and adjust your program accordingly.

Kier says that seasoning a parking lot, which is when you apply brine to a parking lot eight or nine times before the start of the snow season, can also have a big impact.

“It’s obviously an additional expense and extra work, but we have found, as have others who have recommended it to me, that it does make a difference,” Kier says. “You do get better results when you season the parking lot before the start of the season.”

As for other best practices, Kier advises if you’re using the same truck to plow snow as to apply brine, to remove your brine bar after anti-icing so you’re not backing over snowbanks and snapping off the brine equipment. He says landscapers also need to be mindful when transporting these liquid loads.

Making a sudden stop at a traffic light can cause your vehicle to lurch forward and hit the car in front of you when 300 gallons of brine slams into the front of the tank.

Kier says that his company doesn’t use brine on small parking lots, as they don’t find it worth it. He says it needs to be an acre or larger to make it worth their while.

“We don’t charge our customers for using the brine,” Kier says. “The way we do it is we use brine on parking lots where it’s an all-inclusive contract, or we were going to have to pay for the rock salt that we were going to use on that parking lot. So instead, we’re using brine, which reduces how much salt we need to put down, which in turn allows us to make more money on the same job by not having to use as much salt.”

When to consider making your own salt brine

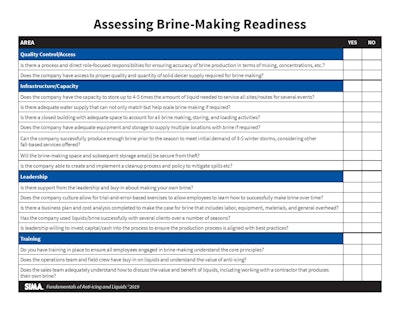

Birch says SIMA advises landscapers to purchase brine and get good at applying liquids first before diving into making your own brine. SIMA also offers a checklist to assess if your company is prepared for this addition. You can also read more about the costs that come with brine making here.

Graphic: SIMA

Graphic: SIMA“Anyone could take a bucket and figure out how to weigh enough salt to make 23.3 percent solution in that bucket of brine,” Birch says. “But to produce it at a scale that meets the output that’s needed for the company, to make sure that there’s quality control and consistency because the last thing you want is poor quality brine out on a property, you can create an ice rink pretty quick, the safety practices and the proper equipment to make the brine, we don’t consider that something you jump into.”

Kier says that if a landscaper has enough volume to justify the costs of the equipment, has a good space for brine maker and the time to make the brine, then they can start considering making their own.

“If you want to make your own brine, it’s going to be very costly at first,” Kier says. “But you can literally save enough on brine in one year to pay for that equipment.”

Stacho says you can make brine for half the cost per gallon from a supplier.

“It’s going to be different for everybody, depending on how much they paid for salt and how much they paid for labor and how much they paid for their equipment,” Kier says. “We make our own brine and the brine costs us about 13 cents a gallon, including the salt and the labor. If we were to buy that same brine and have it delivered, we would probably be paying 60 or 70 cents a gallon.”

A considerable amount of effort must go into making your own brine and without a business plan and elements like quality control, things can backfire quickly. For instance, if you make a 30 percent solution of sodium chloride, the salt is going to crystallize and fall to the bottom of the tank and what’s left is plain water.

“Say you put in a 30 percent solution in your spray tank,” Kier says. “You go out into the parking lot and you spray but you don’t realize the salt is crystallized and fallen to the bottom of your tank and you’re spraying plain water out onto the parking lot; you’re going to get ice.”

Birch acknowledges that in-house brine making is a very advanced step in the world of liquids.

“If you want to get your feet wet with anti-icing, start with a treated salt and anti-ice with the treated salt,” Birch says. “Then, take the step to liquids from there, and then purchase that liquid and get good at applying it. Get a customer base that is accepting of it. Work out the application challenges and learning curve and create a business case to make your own over time.”