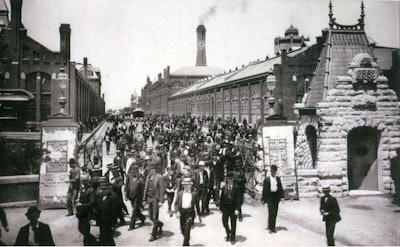

Workers leave the Pullman Palace Car Works.

Workers leave the Pullman Palace Car Works.Photo: Wikipedia

Labor Day is today and for many it means the end of summer and the chance for one last big party. But this day is actually dedicated to the American worker.

According to the Department of Labor, the holiday is a “yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity and well-being of our country.”

The holiday came about during a time when the average American worker had 12-hour shifts and seven-day work weeks with abysmal working conditions. Labor unions began to form in the late 18th century and organized strikes and rallies for better wages and conditions.

The first Labor Day

The first Labor Day was held Sept. 5, 1882, in New York City and it almost didn’t happen at all, as the Grand Marshall of the parade, William McCabe, arrived that morning with very few marchers and no music.

Then, two hundred marchers from the Jewelers Union of Newark Two arrived on a ferry along with a band. McCabe and his followers fell in line behind them and soon spectators and others joined in, and final reports say the numbers of marchers were as many as 10,000 men and women. The parade traveled from City Hall to Union Square.

Afterward, the workers enjoyed in the festivities including speeches on workers’ rights, a picnic and “large beer kegs…mounted in every conceivable place,” according to the Department of Labor.

The father of Labor Day

As for the founder of the day, there is some controversy over who first proposed the idea.

Peter J. McGuire, general secretary of the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and co-founder of the American Federation of Labor, was credited with advocating it first, suggesting the day fall somewhere between the Fourth of July and Thanksgiving, saying it “would publicly show the strength and esprit de corps of the trade and labor organizations,” according to The Conversation.

Yet others argue that it was actually Matthew Maguire, a machinist and secretary of the Central Labor Union (CLU), who championed the holiday.

Becoming a federal holiday

Regardless of who had the idea first, the concept caught on quickly, and with Oregon being the first state to pass a law, it was made a holiday on February 21, 1887.

Others followed suit and by 1894, 23 states had adopted the holiday to honor workers. Labor Day was finally made a national holiday on June 28, 1894, in the wake of a particularly dark piece of American labor history.

Earlier that year, employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company in Chicago went on strike protesting wage cuts.

In a show of solidarity, American Railway Union (ARU) leader Eugene Debs said no ARU members would work on trains that included Pullman cars, crippling the railroads west of Chicago.

Across the country, 250,000 workers in 27 states had gone on strike, halted rail traffic or rioted. Pullman refused to meet with the strikers and hired replacement workers, worsening the situation.

Eventually, President Grover Cleveland dispatched troops to Chicago to break up the strike, resulting in riots that ended with 37 dead, 57 injured and $80 million in damages.

In an attempt to repair ties with American workers and make peace with the unions, Cleveland signed the bill marking the first Monday in September to be a legal holiday known as Labor Day shortly after the Pullman strike.

Rep. Lawrence McGann (D-IL) who was on the Committee on Labor, worded it best when penning a report that supported the addition of the holiday.

“Nothing is more important to the public weal than that the nobility of labor be maintained,” McGann wrote. “So long as the laboring man can feel that he holds an honorable as well as useful place in the body politic, so long will he be a loyal and faithful citizen…Workingmen are benefited by a reasonable amount of rest and recreation. Whatever makes a workingman more of a man makes him more useful as a craftsman.”

So, this year as you enjoy your day off (or spend it working depending on how busy you are), remember that this is a day that is meant to recognize you, your workers and how your hard work helps this country.